By Allison Aubrey

Listen Now [8 min 54 sec]

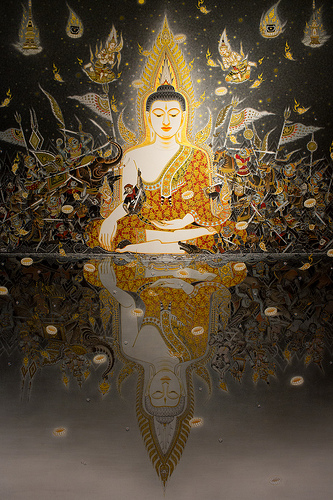

A meditation class inside the Dharma Hall at the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies. Courtesy Barre Center for Buddhist Studies

Morning Edition, July 26, 2005 · People who meditate say it induces well-being and emotional balance. In recent years, a group of neuroscientists has begun investigating the practice, dubbed "mindfulness." As NPR's Allison Aubrey reports, they are exploring the hypothesis that meditation can actually change the way the brain works.

Morning Edition, July 26, 2005 · People who meditate say it induces well-being and emotional balance. In recent years, a group of neuroscientists has begun investigating the practice, dubbed "mindfulness." As NPR's Allison Aubrey reports, they are exploring the hypothesis that meditation can actually change the way the brain works.

Web Extra: Mindfulness for the Masses

By Katie Unger

But the rigors of the scientific method might never have been applied to studying the practice of meditation if it weren't for a vocal population of scientist-meditators. For decades, several of these individuals have been spreading the word about the beneficial effects of this traditional Eastern practice to the Western world.

In 1998, Dr. James Austin, a neurologist, wrote the book Zen and the Brain: Toward an Understanding of Meditation and Consciousness. Several mindfulness researchers cite his book as a reason they became interested in the field. In it, Austin examines consciousness by intertwining his personal experiences with Zen meditation with explanations backed up by hard science. When he describes how meditation can "sculpt" the brain, he means it literally and figuratively.

Before Austin, others had aimed to teach meditation to individuals without experience and without interest in spirituality, people who hoped to reap mental and physical health benefits. In 1975, Sharon Salzberg and Jack Kornfield co-founded the Insight Meditation Society in Barre, Mass., where they continue to practice and teach meditation. Salzberg has written several books, including Faith and Lovingkindness: The Revolutionary Art of Happiness. Kornfield holds a Ph.D. in clinical psychology and trained as a Buddhist monk in Thailand, Burma, and India. He's written an introduction to the field, called Meditation for Beginners.

Jon Kabat-Zinn brought mindfulness into the mainstream by developing a standardized teaching method that has introduced multitudes of beginners to the practice of meditation. In 1979, he founded the Stress Reduction Clinic at the University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center in Worcester. He is professor emeritus of the university's medical school. Kabat-Zinn has written several books that show readers how to incorporate meditation into their daily lives.

One center with which Kabat-Zinn has had a long-standing association -- the Mind and Life Institute -- took a particular interest in partnering "modern science and Buddhism -- the world's two most powerful traditions for understanding the nature of reality and investigating the mind." The institute sponsors scientific conferences for meditation researchers. At the most recent one, scientists discussed how meditation might change activity levels in the brain.

Some 150 centers around the country are shaped in the mold of Kabat-Zinn's Stress Reduction Clinic, and about 150 more teach meditation with slightly different philosophies.

More than 1,000 peer-reviewed scientific articles have been published on the subject of meditation. Until recently, most of them simply observed correlations between meditating and improved mood or decreased disease symptoms. But with so many scientists -- and thousands of consumers -- becoming "believers" in meditation, researchers seek to move beyond simply showing that meditation can influence the brain, to knowing exactly how that influence is accomplished.

Katie Unger is an intern for NPR's science desk.

No comments:

Post a Comment