Wisdom Quarterly (edited and expanded from Wikipedia entry for Yama)

"Death's death" (see below), Tibetan gilded figurine (British Museum/Wikipedia)

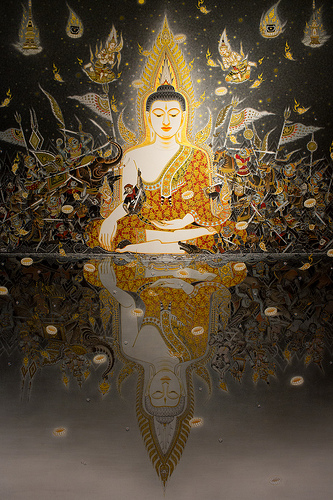

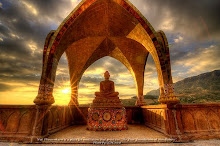

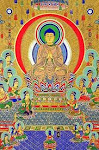

Yama is the name of the Buddhist judge of the dead, a wrathful deity, and dharmapala who presides over the Buddhist purgatories (narakas, nirayas, or impermanent hells).

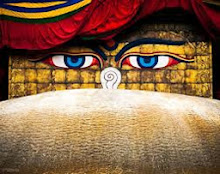

Yama is the name of the Buddhist judge of the dead, a wrathful deity, and dharmapala who presides over the Buddhist purgatories (narakas, nirayas, or impermanent hells).  In Tibet's Vajrayana Buddhism, Yama (Gshin.rje) is regarded with horror as the prime mover of Saṃsāra. He is also revered as a guardian of spiritual practice. In the popular "Wheel of Life" mandala, all of the realms of rebirth are depicted between his monstrous jaws or in his arms. Yama is sometimes shown with a consort, Yami, whose name is associated with "night" in Sanskrit.

In Tibet's Vajrayana Buddhism, Yama (Gshin.rje) is regarded with horror as the prime mover of Saṃsāra. He is also revered as a guardian of spiritual practice. In the popular "Wheel of Life" mandala, all of the realms of rebirth are depicted between his monstrous jaws or in his arms. Yama is sometimes shown with a consort, Yami, whose name is associated with "night" in Sanskrit.Yama in Theravāda Buddhism

Yama is understood by Buddhists as a god of the dead, supervising the various Buddhist "hells." His exact role is vague in canonical texts. It is made clearer in elaborate tales, extra-canonical texts, and popular beliefs -- which are not always consistent with Buddhist philosophy.

In response to Yama's questions, ignoble people often answer that they failed to consider the karmic consequences of their reprehensible actions. As a result they end up in brutal (infernal) worlds until that unwholesome action has sufficiently exhausted its result.[2] The residual effects may not exhaust themselves and they find release only to suffer for that action again in the future.

[For reasons that are hard to accept, and only slightly less difficult to understand through the Abhidharma, actions performed in the human world have disproportionate consequences when they mature in the future. One act of generosity, if it matures at the right moment, which is very hard to depend on, can lead to another human life of great wealth. Simply abstaining from breaking the Five Precepts can lead to a lower heavenly rebirth. A single reprehensible act can lead one to be reborn in a woeful destination with essentially no way to escape. Performing one of the Ten Courses of Unwholesome Action, for example, can dog one over many lives. It alone can take one to a painful rebirth. And if it becomes a habit or character trait, it can snowball until one is doomed with a snowball's chance in hell.]

[For reasons that are hard to accept, and only slightly less difficult to understand through the Abhidharma, actions performed in the human world have disproportionate consequences when they mature in the future. One act of generosity, if it matures at the right moment, which is very hard to depend on, can lead to another human life of great wealth. Simply abstaining from breaking the Five Precepts can lead to a lower heavenly rebirth. A single reprehensible act can lead one to be reborn in a woeful destination with essentially no way to escape. Performing one of the Ten Courses of Unwholesome Action, for example, can dog one over many lives. It alone can take one to a painful rebirth. And if it becomes a habit or character trait, it can snowball until one is doomed with a snowball's chance in hell.]

However, as a king, Yama's rule is considered just.[3] After all, it is not the judge who condemns one to the consequences of actions one has willed and carried out. It is a person's own doing by one's choice of actions. We are always free to choose, even when we insist we have no choice. Having no choice is tantamount to having no imagination, no ability to see things in another way, to see an alternative like simply stopping.

However, as a king, Yama's rule is considered just.[3] After all, it is not the judge who condemns one to the consequences of actions one has willed and carried out. It is a person's own doing by one's choice of actions. We are always free to choose, even when we insist we have no choice. Having no choice is tantamount to having no imagination, no ability to see things in another way, to see an alternative like simply stopping.In fact, in popular belief in Theravādin Buddhist countries, Yama does living beings a great favor: Before they ever end up being judged at death, the god or king of the dead sends old age, disease, punishments, and other calamities among humans as warnings to behave well.

Sometimes there are thought to be several Yamas, each presiding over a distinct hellish world. Theravāda sources sometimes speak of two Yamas or four Yamas.[4]

- Death is a journey; prepare for it

- Buddhism, Halloween, and Ghosts

- VIDEO: Buddhist hells on Thai temple walls

- The gods the Greeks and others once understood

*NOTE: A Tibetan origin myth explains that once upon a time, a holy man was told that if he meditated for the next 50 years, he would achieve enlightenment. He meditated in a cave for 49 years, 11 months and 29 days, until he was interrupted by two thieves who broke in with a stolen bull. After beheading the bull in front of him, they ignored his requests to be spared for but a few minutes and beheaded him as well. In his near-enlightened fury, he became Yama, the god of Death, took the bull's head for his own, and killed the two thieves, drinking their blood from cups made of their skulls. Still enraged, he decided to kill everyone in Tibet, who prayed to the bodhisattva Mañjuśrī, who took up their cause and transformed himself into Yamāntaka ("Death's death") similar to Yama but ten times more powerful and horrific. In their battle, everywhere Yama turned, he found infinite versions of himself. Mañjuśrī as Yamāntaka defeated Yama, and turned him into a protector of Buddhism. He is generally considered a wrathful deity.

*NOTE: A Tibetan origin myth explains that once upon a time, a holy man was told that if he meditated for the next 50 years, he would achieve enlightenment. He meditated in a cave for 49 years, 11 months and 29 days, until he was interrupted by two thieves who broke in with a stolen bull. After beheading the bull in front of him, they ignored his requests to be spared for but a few minutes and beheaded him as well. In his near-enlightened fury, he became Yama, the god of Death, took the bull's head for his own, and killed the two thieves, drinking their blood from cups made of their skulls. Still enraged, he decided to kill everyone in Tibet, who prayed to the bodhisattva Mañjuśrī, who took up their cause and transformed himself into Yamāntaka ("Death's death") similar to Yama but ten times more powerful and horrific. In their battle, everywhere Yama turned, he found infinite versions of himself. Mañjuśrī as Yamāntaka defeated Yama, and turned him into a protector of Buddhism. He is generally considered a wrathful deity.

No comments:

Post a Comment