Ultimate Truth

Wisdom Quarterly (Palikanon.com: paramattha)

The Buddha repeatedly mentioned his reservations about using conventional speech. For example, in The Long Discourses (DN 9):

The Buddha repeatedly mentioned his reservations about using conventional speech. For example, in The Long Discourses (DN 9):

Paramattha-sacca: "Truth (term, exposition) that is true in the highest or ultimate sense," as contrasted with the "conventional truth," which is also called "commonly accepted truth."

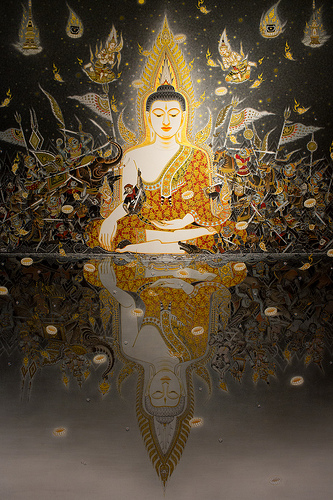

The Buddha sometimes explains the Dharma using conventional (vohara) language. But sometimes he uses the philosophical mode of expression in accordance with undeluded insight into reality.

In this ultimate sense, existence is a process of physical and mental phenomena. In it and even beyond it, there is no real ego-entity. There is no abiding substance to be found. So whenever the sutras speak of a person, or the rebirth of a being, this must not be taken as being valid in the ultimate sense. It is merely conventional mode of speech.

It is one of the main characteristics of the Abhidharma ("Higher Teaching"), as distinct from most of the Sutras ("Discourses"), that it does not employ conventional language. It deals only with ultimates, realities in the highest sense (paramattha-dharma).

Language is not something to cling to ("Talking With Buddha," Empty Mind Films)But in sutras as well there are many expositions in terms of ultimate language. For example, this happens wherever the texts deal with the aggregates, elements, sense-bases, and their components or whenever the Three Marks of Existence are applied.

The majority of sutra texts, however, use conventional language. It is appropriate in a practical or ethical context. It would be confusing or hollow to say, for example, "The aggregates feel shame," and so on even if ultimately this is the case.

It should be noted, however, that even statements by the Buddha that are couched in conventional language are called "truth" for they are correct on their own level. It does not contradict the fact that such statements ultimately refer to impermanent, unsatisfactory, and impersonal processes.

The two types of truth -- ultimate and conventional -- appear in that form only in the commentaries. But they are implied in a sutra-distinction of "explicit (or direct) meaning" (nītattha) and "implicit meaning (to be inferred)" (neyyattha).

The term "ultimate" (paramattha), in the sense used here used, occurs in the first paragraph of the Kathāvatthu, a work in the Abhidharma. (See Guide to the Abhidhamma, p. 62). See also S.I. 25. The commentarial discussions on these truths (Commentary to DN 9 and MN 5) have not yet been translated in full. On these see K.N. Jayatilleke's Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge (London, 1963, pp. 361 ff). In Mahāyana Buddhism, of which Zen is a variety, the Mādhyamika school has given a prominent place to the teaching of the two truths.

No comments:

Post a Comment