Kick up the blue ocean and the whole Earth flies like dust. Shout apart the white clouds and the vast sky is crushed like powder. Though you strictly perform the right decree, that is still only half enough. With the great function fully manifested, how can it be applied?

MAIN CASE

Attention! At Nansen's place one day the monks of the east and west halls were arguing about a cat. Seeing this, Nansen held up the cat saying, "If you can say a word, I won't cut it in two." The assembly made no response. Nansen cut the cat.

Nansen later told Joshu what happened. Joshu took off his straw sandals and, placing them on his head, went out.

Nansen remarked, "If you had been here, you could have saved the cat."

APPRECIATORY VERSE

All monks of both halls were arguing.

Old Teacher King could put right and wrong to the test.

By his sharp knife cutting, the shapes were both forgotten.

A thousand ages love an adept man.

The Way is still not overthrown.

The good listener's indeed appreciative.

For cleaving the mountain to free the river only Laiu is honored.

For smelting stone and mending heaven only Joka is capable.

Old Joshu has his own style;

putting sandals on the head is worth a little.

Coming upon differences, he's still a luminous mirror;

true gold does not mix with sand.

MAIN CASE

Attention! At Nansen's place one day the monks of the east and west halls were arguing about a cat. Seeing this, Nansen held up the cat saying, "If you can say a word, I won't cut it in two." The assembly made no response. Nansen cut the cat.

Nansen later told Joshu what happened. Joshu took off his straw sandals and, placing them on his head, went out.

Nansen remarked, "If you had been here, you could have saved the cat."

APPRECIATORY VERSE

All monks of both halls were arguing.

Old Teacher King could put right and wrong to the test.

By his sharp knife cutting, the shapes were both forgotten.

A thousand ages love an adept man.

The Way is still not overthrown.

The good listener's indeed appreciative.

For cleaving the mountain to free the river only Laiu is honored.

For smelting stone and mending heaven only Joka is capable.

Old Joshu has his own style;

putting sandals on the head is worth a little.

Coming upon differences, he's still a luminous mirror;

true gold does not mix with sand.

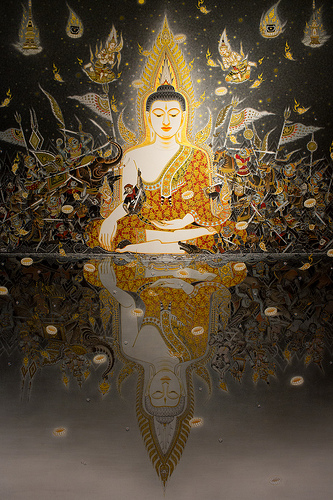

(Clothcompany/Flickr.com)

(Clothcompany/Flickr.com)“Your vision will become clear only when you can look into your own heart. Who looks outside, dreams; who looks inside, awakes.”

- Carl Jung

- Carl Jung

What the blank?

Mara Schaeffer, MS

When I first read this koan, I was horrified! Chinese Zen practitioners must have been depraved to act in such an un-Buddhist way, breaking the first precept by taking life.

When I first read this koan, I was horrified! Chinese Zen practitioners must have been depraved to act in such an un-Buddhist way, breaking the first precept by taking life.As a vegetarian and a cat lover, I felt the only "true" Buddhists were those who honored at least the first precept. Zen must have become corrupt: The koan describes a community divided into hostile sides, unwavering in their positions, much like the world today.

Then the PasaDharma Koan Study Group brought me to a deeper understanding of this koan, sending me in search of meaning on a more profound level: I read several traditional Zen commentaries without finding them particularly helpful. I also practice dream work in the context of depth psychology, and it occurred to me that this koan was similar to a nightmare. Dreams and koans speak in metaphor and symbols.

Both koans and dreams can therefore pierce us with images that challenge our clutched beliefs, probing our hidden pain, and teasing us with the possibility of personal transformation -- if we interact with them.

Committing to being aware here and now is a commitment to bringing into awareness the negative “seeds” of our unconscious. Only then is there any hope of accepting and/or transforming them with understanding and compassion.

The Koan

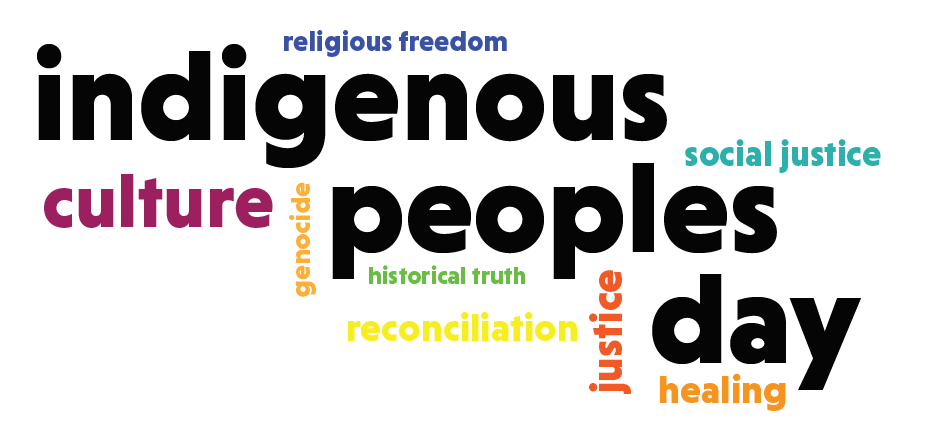

The first two images presented are those of division and fragmentation. The blue ocean of serenity has been kicked up, throwing the Earth it supports into a scattering of dust. The blue tranquility of heaven is crushed like powder with loud shouts of conflict, antagonism, arguments, and dissension.

These images reflect the collective of the monastery. It is deeply divided into two camps warring against each other rather than deepening their practice and experiencing enlightenment.

On a personal level, it is like the warring thoughts and hindrances that swirl up through the imagination of a meditator during sitting, distracting the mind and, in the words of Paramahansa Yogananda, “kicking over the milk bucket of our spiritual bliss.”

Zen Master Nansen, as leader of the monastery, had to confront the problem directly to save the sangha (community) from itself. He held up the cat, possibly the only living being commonly loved by both camps. Or possibly the cat had committed some heinous act, playfully torturing and killing a pet of importance to the monks and/or village that supported the monastery.

In dream work, the cat often represents relatedness and the emotional connection of people to loved ones, as well as the inner feminine. The bigger the cat, the bigger the passion it represents. The cat was sacred to the Germanic goddess of love, Freya.

Many of the goddesses (devis) of India who embody the active energy (shakti) and power of male deities (devas) are pictured riding lions or tigers. In the ancient Pali Canon, the Buddha refers to himself and other prominent disciples as if they were stately lions, lords of the jungle or at least one domain, proclaiming the Dharma with a "lion’s roar" in the spiritual milieu of ancient India.

Desktop Zen rock gardening (smallcricket.com)

Desktop Zen rock gardening (smallcricket.com)For the monks in the monastery, the cat might represent the projected anima, or “inner woman,” the sensitive feeling or emotive part of a man's personality. This can become a state described as anima possession when negative feelings overwhelm the personality with unconscious emotionality in the form of moods, restlessness, sentimentality, and even promiscuity -- imagined or real.

The whole monastery was in the grip of this "catty" nastiness, anima possessed behavior, which threatened the purpose of its existence.

Perhaps Nansen as the leader felt he had to do something dramatic and direct with the hope of shocking the community into seeing and instigating corrective action.

As the character Otter says to a similarly dissolute, anima-possessed "Animal House" fraternity:

“I think we have to go all out. I think that this situation absolutely requires a really futile and stupid gesture be done on somebody's part!”

Nightmares come from the so called “stupid” or irrational part of our psyche.

Nansen offers: "If you can say a word, I won't cut it." But the monks are so caught up in their divisiveness and conflict, no one responds. So Nansen performs a blood sacrifice: primitive, messy, barbaric, perhaps in an attempt to break through their destructive pettiness, which is poisoning their spiritual life.

On a personal level, when a murder takes place in a dream, we need to ask ourselves, “What part of my life have I been murdering?” That is, what part needs to be acknowledged and brought into consciousness?

How did the monks react to the cat mutilation? Was it with my revulsion and horror? The text does not say. The only reaction recorded was that of Joshu, who puts his sandals on his head. What could this gesture mean?

Sandals are the lowliest article of clothing, in contact with the soil, thrown at political leaders as an act of protest who lose our support and become dirty by their corrupting actions. The Jungian therapist and author Robert Johnson writes about the similarities between the soles of the feet and soul as the entrance of spirit into the body, which in medieval Christianity was believed to always be through the feet.

Sandals are the lowliest article of clothing, in contact with the soil, thrown at political leaders as an act of protest who lose our support and become dirty by their corrupting actions. The Jungian therapist and author Robert Johnson writes about the similarities between the soles of the feet and soul as the entrance of spirit into the body, which in medieval Christianity was believed to always be through the feet.The architecture of old Gothic churches was laid out to represent the prone body of Jesus. The entrance and exit to the building was always built where the soles of Jesus’s feet would be -- a common motif in the mystic East Indian Buddhist/Hindu theme foreign to Judaism and Islam farther West.

As Buddhists, kinhin (walking meditation) is often a part of our practice, using our feet and the grounding experience of walking to focus our meditation. Modern Vietnamese Zen Master Thich Nhat Hahn charges us to “kiss the Earth with our feet” when we walk.

What did Joshu's sandals symbolize? Was he expressing an intuitive movement of opening up to feeling below and beyond any conceivable intellectual “stand”?

In response to both events -- the insensate murder of the cat and the spiritual death of the sangha -- the only appropriate reaction would be that of shock and silent grieving, a deep mourning that extended beyond the personal.

Do we mourn as deeply when our practice is disturbed and distracted, split from its purpose, murdering our precious “here and now” consciousness?

There is something about the profound pain of suffering which is as deep as the disturbed ocean. But like the ocean it is not bottomless. There comes a time when one’s grief touches ground and moves toward healing. Values are repositioned and redefined.

The monkey mind during sitting becomes less distracted -- or at least less distracting when we learn to simply watch it rather than becoming involved in its ceaseless machinations -- and the Buddha mind or enlightened mind (bodhicitta) grows stronger.

Existence goes on like the blue sky where our grief and even our lives and communities condense and dissolve like clouds over time. Maybe the community of monks, united in grief and shock at the loss of their beloved cats, which could have been the source of their petty argument (Who owns this cat, east or west halls?) overcame their conflicts, and returned to their practice.

Some in the study group noted that this story was just like the more shocking Biblical version familiar to Westerners: a tale of a human baby threatened with being cut in two to settle an ownership dispute. Surely the real mother will cry out that the impostor mother should take her child rather than see her child come to any harm. But the impostor, not possessing that affinity and nurturing impulse, reveals herself. The child is then given to the real mother who cared enough to relinquish her attachment to it. Maybe, just maybe, no cat was actually harmed in the making of this koan. Zen Master King Solomon Cuts a Baby

Some in the study group noted that this story was just like the more shocking Biblical version familiar to Westerners: a tale of a human baby threatened with being cut in two to settle an ownership dispute. Surely the real mother will cry out that the impostor mother should take her child rather than see her child come to any harm. But the impostor, not possessing that affinity and nurturing impulse, reveals herself. The child is then given to the real mother who cared enough to relinquish her attachment to it. Maybe, just maybe, no cat was actually harmed in the making of this koan. Zen Master King Solomon Cuts a Baby

Joshu’s presence, like a “luminous mirror,” reflects the storm around him clearly but remains unperturbed at his depths. He is like the element “gold that does not mix with sand.” Only what he represents can still save the symbolic “cat” in all of us.

Wisdom

We are so quick to judge, to react, to believe, identify, and cling to "our" minds. The wisdom of this koan eventually spoke to me.

We are so quick to judge, to react, to believe, identify, and cling to "our" minds. The wisdom of this koan eventually spoke to me.Recently a loved one from my youth, whom I had friended on Facebook, started preaching hateful political tirades. Shocked, I was ready to “cut” our friendship by the ultimate modern act of exile -- unfriending him on Facebook.

But by more closely reading his posts, I realized that beneath his anger was the same disappointment and pain with the political reality I had been feeling. Only he had reacted differently, angrily, violently, caught up in his own hindrances and confusion, which made him want different solutions that were, in their own extreme, as biased and opinionated as my own. Perhaps someday a dialogue will be possible.

Of course, like a dream, the truth of the koan is much closer to poetry than to prose. Words, ideas, even interpretations all fall short of the pure, silent eloquence of living images.

Understanding the translucent language of the koan and the nightmare can help us move toward a deeper awareness of the living reality they reflect. Then we can choose wisely like Joshu between the sand and the gold. We can reload our efforts to deepen our practice with renewed insight. Or as Nanrei Kobori-Roshi prompts us:

“Stop splashing along the surface with all your words and concepts...dive down deep into zazen.”

1 comment:

that is a Koan I am working on at the moment. I love the Solomon story. It helps

Post a Comment