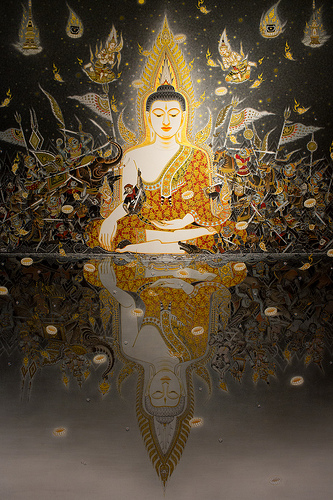

Countless devas, devis, brahmas (extraterrestrial divinities), wanderers (shramans), brahmins, monks, nuns, and lay followers came to the Buddha for guidance. As a universal teacher, he welcomed and helped them all.

Countless devas, devis, brahmas (extraterrestrial divinities), wanderers (shramans), brahmins, monks, nuns, and lay followers came to the Buddha for guidance. As a universal teacher, he welcomed and helped them all."Suppose a monastic were to say, 'Friends, I heard and received this from the venerable one's own lips: This is the Dhamma, this is the Discipline, this is the Master's Teaching.' In that case, monastics, you should neither approve nor disapprove of those words.

"'Assuredly this is not the word of the Buddha; it has been wrongly understood by this monastic, and the matter is to be rejected.' But where on such comparison and review they are found to conform with the discourses or the discipline, the conclusion must be:

"'Assuredly this is the word of the Buddha; it has been rightly understood by this monastic'" (DN 16, The Buddha's Last Days, Mahāparinibbāna Sutta).

The authentic teachings of Gotama (Sanskrit, Gautama) the Buddha have been preserved, handed down, and are to be found in the Three Divisions of the Dharma (literally, "three baskets," ti = three + piṭaka = collections of scriptures). All of the Buddha's teachings, when they were originally written down on ola palm leaves, were stored in one of three baskets according to subject matter.

The Buddha had many prominent female disciples in an apparently smaller separate but equal Bhikkhuni Order that monks later subordinated by the institution of eight additional rules (garudhammas) for women. It has been claimed that the Buddha instituted these additional rules as a condition for female ordination -- an assertion contradicted by textual evidence that modern Theravada monks either do not know or choose to ignore to keep women out. It seems these sexist rules were a later fabrication. The issue is extremely important because based on these rules some assert that no woman can now legitimately gain the higher ordination in Theravada Buddhism to be a full nun and instead at best can only hope to be a ten precept holder living as a monastic without the rights and privileges full ordination would confer. For the Dharma to survive and prosper in modern times, particularly in the West, women are absolutely needed. Anyone who stands against them based on specious, fabricated, and unvetted "rules" harms the Dharma and limits how long it will survive to help everyone. Therefore, it is an issue of the utmost importance for monks interested in preserving the tradition as well as Buddhist women in the world today.

The Buddha had many prominent female disciples in an apparently smaller separate but equal Bhikkhuni Order that monks later subordinated by the institution of eight additional rules (garudhammas) for women. It has been claimed that the Buddha instituted these additional rules as a condition for female ordination -- an assertion contradicted by textual evidence that modern Theravada monks either do not know or choose to ignore to keep women out. It seems these sexist rules were a later fabrication. The issue is extremely important because based on these rules some assert that no woman can now legitimately gain the higher ordination in Theravada Buddhism to be a full nun and instead at best can only hope to be a ten precept holder living as a monastic without the rights and privileges full ordination would confer. For the Dharma to survive and prosper in modern times, particularly in the West, women are absolutely needed. Anyone who stands against them based on specious, fabricated, and unvetted "rules" harms the Dharma and limits how long it will survive to help everyone. Therefore, it is an issue of the utmost importance for monks interested in preserving the tradition as well as Buddhist women in the world today.- The first part is known as the Vinaya Piṭaka containing all of the rules which the Buddha laid down for monks and nuns (and novices).

- The second part is called the Suttaṅta Piṭaka containing the discourses.

- The third part is known as the Abhidhamma Piṭaka containing the psychological [as well as the particle physics] and ethical teachings of the Buddha.

In this way the Buddha's words were preserved accurately and were in due course passed down in the oral tradition of the day from teacher to pupil. Some of the monastics who heard the Buddha teach in person (savakas or "hearers") were arhats -- "noble ones" free of passion, ill-will, and delusion. They were therefore capable of perfectly retaining the Buddha's words. So they ensured the Buddha's teachings would be preserved faithfully for posterity.

Even those devoted monastics who had not yet attained full enlightenment but had reached the three preliminary stages and had powerful, retentive memories could also call to mind word for word what the Buddha had taught and so were worthy custodians of the Doctrine.

There were almost always monastic companions as well as lay disciples present when the Buddha taught. Most of his teachings were to ordinary people. But since monks took it upon themselves to memorize and recite those delivered them -- not the ones delivered to the nuns or exclusively to lay people -- it now seems as if all of the sutras began, "O, monks..." This makes it seem as if the Buddha was only addressing them when he taught, or that this was the case the majority of the time. But we know that he taught almost daily, and most of the settings and circumstances are to ordinary people. This is to the detriment of women today, but it is also to the detriment of lay people and therefore Buddhism in general even as monks experience it. The most famous and significant sutra for lay people is the Sigalovada Sutta, the Advice to Laypeople," which is cobbled together imperfectly from more than one discourse. Where are those other discourses now? The monks did not retain them. With the loss of the Nuns' Order, the sutras addressed to them that they memorized and recited apparently disappeared as well. All that remains is what the monks considered important to retain, which is generally advantageous to them.

There were almost always monastic companions as well as lay disciples present when the Buddha taught. Most of his teachings were to ordinary people. But since monks took it upon themselves to memorize and recite those delivered them -- not the ones delivered to the nuns or exclusively to lay people -- it now seems as if all of the sutras began, "O, monks..." This makes it seem as if the Buddha was only addressing them when he taught, or that this was the case the majority of the time. But we know that he taught almost daily, and most of the settings and circumstances are to ordinary people. This is to the detriment of women today, but it is also to the detriment of lay people and therefore Buddhism in general even as monks experience it. The most famous and significant sutra for lay people is the Sigalovada Sutta, the Advice to Laypeople," which is cobbled together imperfectly from more than one discourse. Where are those other discourses now? The monks did not retain them. With the loss of the Nuns' Order, the sutras addressed to them that they memorized and recited apparently disappeared as well. All that remains is what the monks considered important to retain, which is generally advantageous to them.One such monastic was Ānanda, the Buddha's chosen attendant and constant companion during the last 25 years of his life. Ānanda was kind, intelligent, and gifted with a remarkable ability to remember all that he heard. Indeed, in order to accept the position, it was his express wish that the Buddha always relate to him discourses originally delivered in his absence. Although he was not yet enlightened, he deliberately committed to memory word for word all of the Buddha's sutras.

As a teacher the Buddha exhorted his monk, nun, and lay followers. The combined efforts of these gifted and devoted followers made it possible for the Doctrine and Discipline as taught by the Buddha to be preserved in its authentic state.

The Pāli threefold division of the Dharma and its allied literature exists as a result of the Buddha's discovery of the noble and liberating path of the pure Dharma. This path enables all who follow it to lead a peaceful and increasingly happy life.

Indeed, in this day and age we are fortunate to have the authentic teachings of the Buddha preserved for this and future generations through the conscientious and concerted efforts of his disciples down through the ages.

The Buddha said to his disciples that when he was no longer among them, it was essential that the Saṅgha (monastic community) should come together for the purpose of collectively reciting the Dharma, according to formal oral tradition, precisely as he had taught it.

Buddhaghosa was the greatest ancient Buddhist compiler and commentator, author of both The Path of Purification (Vissudhimagga) and The Path of Freedom (Vimuttimagga), texts important in both Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism.

Buddhaghosa was the greatest ancient Buddhist compiler and commentator, author of both The Path of Purification (Vissudhimagga) and The Path of Freedom (Vimuttimagga), texts important in both Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism.To comply with this instruction the first elders (theras, senior monastics) duly convened a council and systematically organized all of the Buddha's discourses and monastic rules then faithfully recited them word for word in concert.

The teachings contained in the threefold division (Tipitaka) is also known as the "Doctrine of the Elders" (Theravāda). These discourses number several hundred and have always been recited word for word ever since the First Buddhist Council was convened. Subsequently, more councils have been called for a number of reasons, and at every one of them the entire body of the Buddha's teaching has always been recited by the Saṅgha participants together word for word.

- That is, the oral tradition has continued in spite of writing because it is a more faithful form of keeping the Dharma from declining. Why? Words on a page can be altered, but no one can hope to simultaneously altered the memories of many thousands of seasoned monastics all at once. Therefore, change in the words is very slow and takes place only after deliberate debate and consideration. Councils define and settle issues that arise in the living body of the Buddhist community.

They are so designated because of the precedent set at the First Dharma Council, when all the Teachings were recited first by an elder, either Upali in the case of monastic rules or Ananda for other material, of the Saṅgha then chanted once again in chorus by all of the monastics -- for a long time exclusively monks -- attending the assembly.The recitation was judged to have been authentic when and only when it had been unanimously approved as accurate by all of the members of the council. What follows is a brief history of the six councils.

- Why was the First Council convened? It is said that Maha Kassapa called the first gathering of elder monastics in response to unskillful comments uttered by Subaddha, an unwise older man who ordained late in life and was disgruntled at there being so many rules: What all of those comments were is not certain. But according to Culavagga in Vinaya Pitaka, Maha Kassapa overheard Subaddha saying to the other monks who had just heard of the Buddha's attainment of final nirvana: “Friends…since the Buddha is dead, now there is no one to tell us what to do and what not to do. So we can do whatever we want.”

More

- Buddhist Councils (Sangayana) according to the Mahavamsa

- Extra rules for Theravada Buddhist nuns?

- VIDEO: The Buddhist nuns of California

One of the Buddha's greatest disciples is an American scholar-monk alive today. Born on the East Coast, educated on the West Coast, and a long time resident of Sri Lanka as editor of the Buddhist Publication Society, Bhikkhu Bodhi, like his eminent teachers (particularly Ananda Maitreya and Nyanaponika Thera). He has done more to preserve and promote the Pali Canon -- as editor, translator, interpreter, commentator, co-author, and promoter (organizer of ghost translators) -- than anyone alive. He is our longstanding teacher and an inspiration to this publication. Almost every Buddhist alive is familiar with his work even if the name does not sound familiar because of his translation. They have become the standards in English:

Venerable Bhikkhu Bodhi

Rev. Danny Fischer (elephantjournal.com)

Though many know him well as the Pali scholar responsible for prodigious English translations of huge pieces of the Tripitaka, Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi has also emerged in the last few years as one of the globe’s most important and industrious Engaged Buddhist leaders. Born Jeffrey Block in Brooklyn in 1944, he was ordained in the Theravada Buddhist tradition of Sri Lanka at age 28. In 1984, he succeeded the great Ven. Nyanaponika Thera as editor of the Buddhist Publication Society. By 1988, he was named president of the organization. He would hold these positions until 2002, when he returned to the United States. More

Rev. Danny Fischer (elephantjournal.com)

Though many know him well as the Pali scholar responsible for prodigious English translations of huge pieces of the Tripitaka, Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi has also emerged in the last few years as one of the globe’s most important and industrious Engaged Buddhist leaders. Born Jeffrey Block in Brooklyn in 1944, he was ordained in the Theravada Buddhist tradition of Sri Lanka at age 28. In 1984, he succeeded the great Ven. Nyanaponika Thera as editor of the Buddhist Publication Society. By 1988, he was named president of the organization. He would hold these positions until 2002, when he returned to the United States. More

No comments:

Post a Comment