(Via Huffington Post) Usually we know where to look for answers. You know where to go for the weather forecast, and who to call when your car won't start. If you need to find something more esoteric -- who fought the War of the Spanish Succession, or what is the main export of Bangladesh -- there's always Wikipedia.

What about religion? How do we get answers?

What about religion? How do we get answers?

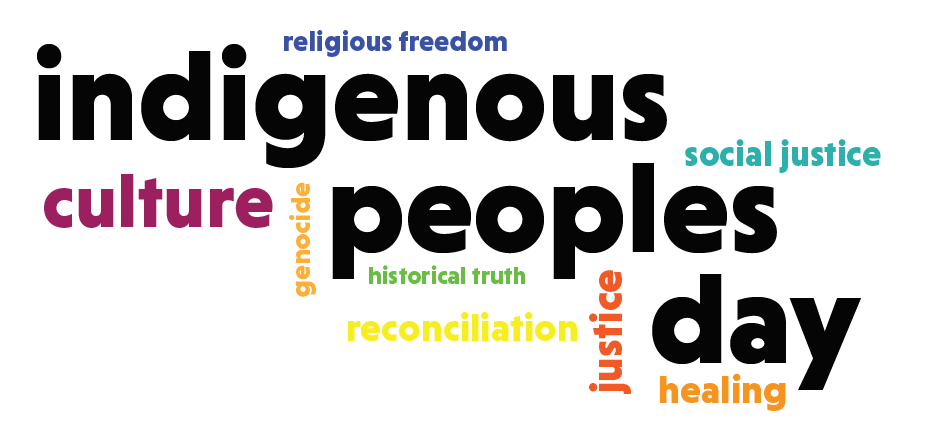

I am not talking about the unknowables -- like where we go when we die [which is different for everyone depending on the conscious state as one passes to be reborn as some dominant, habitual, or fortuitous karma comes to fruition]. I mean more straightforward matters of doctrine or interpretation. There is no shortage of important questions about religion: what exactly is jihad, is yoga a Hindu practice, does Jesus really hate liberals [because he loves hateful right-leaning extremists], and so on. Lots of people will weigh in on these questions--but who should we actually believe?

Holy men, women, and books

Most religion is organized in hierarchies of authority. The world's religions are populated by a constellation of priests, patriarchs, monks, imams, wise women, and gurus. These would seem like the first and last stop in our quest for answers. But not all leaders are the same.

For one thing, there is the question of who gives religious leaders their authority. Even within [patriarchal, hierarchical, fundamental, or papally infallible] Christianity, there are many ways of understanding.... Religious leaders are often expected act as custodians of the faith -- as leaders of a community and keepers of its traditions. However, this is not always the case, because learning and knowledge are not the only paths to spiritual achievement.

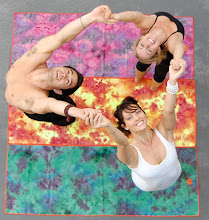

If the path to holiness takes you through mysticism or meditation, it may not necessarily prepare you to answer questions of doctrine. Argue any point of... More

Meditacion-Zen (smallcricket.com)

Meditacion-Zen (smallcricket.com)The ANSWER

Maya S. Putra, Seven, and Andrew Winn, Wisdom Quarterly

IF no one knows or does not know how s/he knows -- the central epistemological question being, "How do we know that what we know is true?" -- is a timeless one.

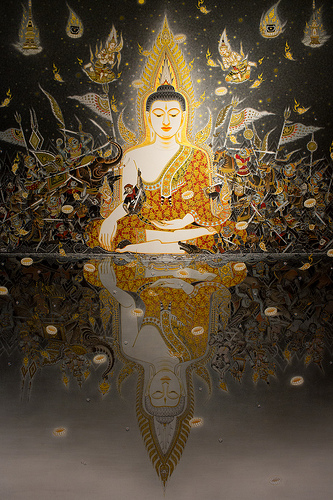

The Buddha emphasized the importance of a teacher. We will not stumble upon it ourselves. (He certainly did not become enlightened or, moreover, a teach of enlightenment by chance, luck, destiny, or spiritual rebelliousness). But we are told that he went without one, which is incorrect and at odds with the texts but makes a nice story for American rebel with our impulsive, irreverent, and independent streaks.

What a real Buddhist teacher teaches is not the ultimate teaching -- not some dogma, some set of beliefs to accept, or pat answers to ultimate questions.

The Buddha's Teachings, and those of teachers who continue in his line, teach the Path-of-Practice that leads to ultimate answers. We need to walk not have a priest or priestess report back to us what it was like. The rarefied peak of the mountain cannot be brought down to us (it would no longer be that down here); we have to climb up there, which is not a struggle but a persistent journey with lots of base camps to replenish ourselves for the quest with the help of others.

One must see and experience "the truth" for oneself. And what is our slogan?

"No one saves us but ourselves

No one can and no one may

We ourselves must tread the path

Buddhas only point the way."

So it's do-it-yourself? NO. It does no good that another has found it if we do not make the Truth our own by practice. Yet, it's not a free-for-all that needs us to reinvent the wheel. The path still exists for us to question, follow, and verify by experience in this very life. There is no need to wait till we die to see if we were right.

The Buddha's Teachings, and those of teachers who continue in his line, teach the Path-of-Practice that leads to ultimate answers. We need to walk not have a priest or priestess report back to us what it was like. The rarefied peak of the mountain cannot be brought down to us (it would no longer be that down here); we have to climb up there, which is not a struggle but a persistent journey with lots of base camps to replenish ourselves for the quest with the help of others.

One must see and experience "the truth" for oneself. And what is our slogan?

"No one saves us but ourselves

No one can and no one may

We ourselves must tread the path

Buddhas only point the way."

So it's do-it-yourself? NO. It does no good that another has found it if we do not make the Truth our own by practice. Yet, it's not a free-for-all that needs us to reinvent the wheel. The path still exists for us to question, follow, and verify by experience in this very life. There is no need to wait till we die to see if we were right.

But the Buddha was a rebel, no?

What we are usually not told is how long it took the Bodhisat to become the Buddha, through lives when he is referred to as a seeker after truth developing the perfections that would enable him to teach it when he found it. He was determined to become a path-finder. For he was not technically a "trailblazer" but a re-discoverer.

And even in his last life, his final rebirth, he had numerous teachers (his parents, his wife, advisors, tutors, Alara Kalama, Uddaka Ramaputta, devas, fellow ascetics involved in the quest, brahmas, and even after becoming the fully enlightened supreme Buddha, he thought it unseemly to be a young ascetic without a teacher, so fundamental was the Indian custom to have a teacher. But he had no equal, no one who could now be his teacher, except that he would psychically look to the past to see what buddhas in the past had done and choices they made; he may even have had access to simultaneous buddhas on other worlds in distant galaxies (world systems) since there can only be one at a time in any world system, and usually there is not even that).

And little mention is made of the crucial fact that when he determined/resolved to become a supreme buddha (samma-sam-buddha) capable of making known, teaching the Path to completion, and establishing an organized monastic institution of practitioners that could keep the message (the Dharma) alive in perpetuity, that is to say when he became a bodhisattva ("being bent on enlightenment"), he possessed all of the requisites to attain full enlightenment under the Buddha Dipankara.

In that past life he had been reborn as Sumedha (shown above with long hair as a prostrate yogi ascetic who lived in a cave in the Himalayan foothills, palms joined, making his aspiration at the sight of Dipankara Buddha). He was an ascetic, who had access to flight either by levitation or some technological means we assume impossible because we are taught that antiquity is always backwards and unvisited until we evolved.

This planet and human life here is, in fact, cyclical more in accordance with a scientific theory called "punctuated equilibrium" in the social rather than biological domain. Who speaks for religion? Whoever can, whoever wants to.

Who should we listen to? Any and everyone, but ultimately what we should be listening for if we want to advance is not final products (philosophies, theories, dogmas, things to put blind faith in) but living practices.

What can I do, what can I refrain from doing, what can I practice, that will lead me to knowing, to knowledge that surpasses all understanding?

What samadhi (absorbed and purifying states of concentration) makes me like a saint, and what vipassana (mindful insight-wisdom) actually makes me enlightened?

Who speaks that truth, points out that path, who should speak for religion?

Buddhist prayer flags fly high in the Himalayas (Bhakti Omwoods/Facebook).

Buddhist prayer flags fly high in the Himalayas (Bhakti Omwoods/Facebook).Other religions will get one to the heavens (none of which, however exalted, are actually eternal), and Buddhism can too. But only Buddhism points the way to final nirvana. If all religions led there, there would be no reason to ever pick a tradition. We could just be all of them or none in particular (which we seem to prefer).

Be none, be agnostic, be atheistic, cling to tradition, but whatever is done, PRACTICE. In that way, you will ultimately be able to speak for yourself with great confidence about what is timeless truth and what is not.

- Dharma Here and Now (Bhutan's Kuensel Online)

- Letters To Young Rationalists

- (No. 09, Bertrand Russell) Morally committed to data and evidence-based search for knowledge as opposed to mere faith and belief

- PHOTOS: 25 things about Christianity

- The world has a Buddhist master: Pa Auk Sayadaw

- Dhammaweb.net: Baby monks-in-training

No comments:

Post a Comment