|

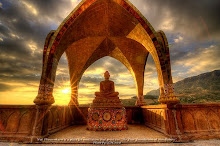

| The Buddha's eyes of wisdom, Maitreya, Thiksey Monastery, Ladakh, India (dailymail.co.uk) |

I often hear Buddhists talk about wisdom and compassion. What do these two terms mean?

Some religions believe that compassion or love (the two are very similar) is the most important spiritual quality, but they fail to develop any wisdom.

The result may be ending up a good-hearted fool, a very kind person with little or no understanding.

Other systems of thought, like science, believe that wisdom can best be developed when all emotions, including compassion, are kept out of the way. The outcome of this is that science has tended to become preoccupied with cold results and has forgotten that science should serve not destroy us or make corporations rich. It is out of greed for money, not hate, that scientists lend their skills to developing nuclear waste, bombs, germ warfare, plastic xenoestrogens, and the like.

Religion sees reason and wisdom as the enemy of emotions like love and faith. Science sees emotions like love and faith as enemies of reason and objectivity. Science progresses, religion declines.

Buddhism, on the other hand, teaches that to be a balanced and complete individual, we must develop both wisdom and compassion. This is the highest wisdom; this is the greatest compassion. It is not dogmatic. Buddhism bases this on actual experience. Buddhism has nothing to fear from science.

According to Buddhism, what is wisdom?

|

| Sensual-pleasure is low, jhana is high (H-K-D) |

At an ordinary level, then, wisdom is to keep an open mind rather than being closed-minded, listening to other points of view rather than being bigoted, carefully examining facts that contradict our beliefs rather than burying our heads in the sand, being objective rather than prejudiced, taking time to form opinions and beliefs rather than accepting the first or most emotional thing that is offered to us, and it means remaining flexible and strong rather than stiff and brittle about what we believe.

We are wise to be ready to change our beliefs when facts that contradict them are presented to us. The Buddha's advice to the Kalama people was not to believe nothing. It was to investigate and see for oneself so that what one believes agrees with one's own experience.

A person who does this is certainly wise and is certain to eventually arrive at higher (liberating) understanding. The path of just believing what we are told would be silly and easy. The Buddha's PATH is a practice that requires courage, patience, flexibility, intelligence, and compassion.

So we arrive at compassion. According to Buddhism, what is compassion?

|

| Imperfect translation has heart in the right place (zazzle.com) |

Like wisdom, compassion is a deeply human quality. Compassion is made up of two words, "co" meaning together and "passion" meaning strong feeling.

And this is what compassion is. When we see someone in distress, we feel their pain as if it were our own -- so naturally we strive to eliminate or reduce their pain. This is compassion (karuna), the active side of love (metta, loving-kindness, friendliness).

All the best in human beings, all the Buddha-like qualities like sharing, readiness to give comfort, sympathy, unselfishness, concern, and caring -- these are all manifestations of compassion.

Notice that in the compassionate person, care and love toward others originates in care and love for oneself. They are not mutually opposed. It is best to care for other while caring for oneself. They are mutually supportive activities.

(Playing the role of martyr makes two people miserable, ourselves and other. We give rise to pride or resentment. Then if someone helps us, we feel guilt. This is no way to practice compassion).

We can really understand others when we really understand ourselves. We can give to others when we give to ourselves. Selflessness does not mean self-abnegation; it means seeing that things are really impersonal so we can give them up, give up clinging, give up greed, give up selfishness. This is wisdom as it feeds compassion.

We will know what's best for others when we know what's best for ourselves. We can feel for others when we feel for ourselves. So in Buddhism, one's own spiritual development blossoms naturally into concern for the welfare of others.

The Buddha's life illustrates this very well. It was not one of sitting in the Himalayas, as he had done in past lives cultivating absorption (jhana) and developing good qualities, simply withdrawn enjoying the bliss of meditation.

He spent six years struggling for his own welfare, striving to be of benefit to the whole of the human world and the devas.

So you are saying that we are best able to help others after we have helped ourselves. Isn't that a bit selfish?

We usually see altruism, concern for others before oneself, as being the opposite of selfishness, concern for oneself before others. Buddhism does not see it as either one or the other but rather as a blending of the two.

Genuine self-concern gradually matures into concern for others as one sees that others are really in the same boat, suffering in many of the same ways, not so different from oneself.

This is genuine compassion, and it is the most beautiful jewel among the many treasures of the Buddha's teachings.

No comments:

Post a Comment