.

|

| Wilshire Grand Tower hovers high in the sky. |

The worker "fell" (more like jumped) from the tower around noon on St. Patrick's Day at the Wilshire Grand Center onto the back edge of a passing car.

It happened at one of the busiest times of day at one of the busiest intersections in downtown Los Angeles, when the streets were thronged with people.

The electrician hit the trunk of the white car, which sat at the corner Wilshire Blvd. and Figueroa St. with his blanket-covered body and a coroner's tent set up hours later. The car did not appear to be that badly damaged.

|

| The City of Los Angeles is backed by mountains with snow after storms (buzzfeed.com). |

.

The woman who was driving did not appear to be seriously physically hurt but was taken to a hospital, city fire officials said. Her psychological damage will be hard to measure. The 73-story skyscraper will be about 1,100 feet tall, or nearly a quarter-mile, when it's completed. A ceremony was held earlier this month when the top beam was hoisted into place on the 73rd floor. The $1 billion office and hotel tower being developed by Korean Airlines Co. Ltd. is expected to open in early 2017.

A ceremony was held earlier this month when the top beam was hoisted into place on the 73rd floor. The $1 billion office and hotel tower being developed by Korean Airlines Co. Ltd. is expected to open in early 2017.

The building is near the Staples Center arena where the NBA's Los Angeles Lakers and Clippers play and is at the center of the bustling and fast-growing financial district of downtown. More

- Killing breaks the Five Precepts; it is unwholesome karma. So it will have unwanted results. Killing oneself (suicide) is killing.

Suicide: A Simple Guide to Life

Robert Bogoda (Wheel 397, Buddhist Publication Society) edited and expanded by Amber Larson, Dhr. Seven, Crystal Quintero (eds.), Wisdom Quarterly

.

|

| What is this skull doing here? Who gives up on life? |

One also learns to face life's losses, failures, disappointments, and adversities calmly, without complaining. For one knows, or at least cultivates confidence (conviction), that they are often the result of our past deeds engaged in in ignorance, motivated by craving, aversion, or fear.

Why me?

If we asks ourselves: "WHY has this happened to me?" it is usually a complaint rather than a question.

The answer, if we wanted it, can be expressed in terms of actions-and-results. This gives great hope because the same regularity still applies! What we do now, right now, will bear fruit. Is there any time to complain or feel sorry for ourselves? Would it not be better to engage in plans, words, and deeds motivated by nonignorance, nongreed, nonhatred? Karma means hope and possibility. We steer our ship, often poorly and blindly, but we steer it, and we can get better at steering it.

Why me?

If we asks ourselves: "WHY has this happened to me?" it is usually a complaint rather than a question.

The answer, if we wanted it, can be expressed in terms of actions-and-results. This gives great hope because the same regularity still applies! What we do now, right now, will bear fruit. Is there any time to complain or feel sorry for ourselves? Would it not be better to engage in plans, words, and deeds motivated by nonignorance, nongreed, nonhatred? Karma means hope and possibility. We steer our ship, often poorly and blindly, but we steer it, and we can get better at steering it.

One will solve problems to the best of one's ability and will adjust oneself to the new situation when external change is not possible. One need not act rashly, nor fall into despair, nor try to escape difficulties by resorting to drink, drugs, or suicide, as so often happens in modern times wracked with doubt and persistent skepticism. Such conduct only shows emotional immaturity and ignorance of the Buddha's teachings, the Dharma.

For a genuine Buddhist, then, one's everyday activities (karma, choices, willed actions), by way of thought, word, and deed, are more important than anything else in life.

A proper understanding of the Buddhist law of karma and the countless rebirths we are wandering through is essential for happy and sensible living and for the welfare of the world, the good of others and ourselves. In the Buddha's own words:

The slayer gets a slayer in turn;

The conqueror gets one who conquers;

The abuser wins abuse, the annoyer frets.

Thus by the evolution of the deed,

A person who spoils is spoiled in turn.

— Kosala Samyutta (SN), trans. by Sir Robert Chalmers

|

| "Call the police, there's a jumper on the ledge." [Uh, never mind.] (Gareth Cowlin) |

Although we imagine ourselves to be a self -- a real and enduring substantial individual -- according to the Buddha's teaching we are, ultimately speaking, more like a flame-like process, an ever-changing combination of matter and mind, no element of which is the same for two consecutive moments.

All of the components of our being are impermanent, unsatisfactory, and devoid of self (in flux, disappointing, and insubstantial. Life is not a "being," an identity; it is a becoming, not a product, but a process.

There is in actuality no doer -- again, ultimately speaking -- only a doing, no thinker, feeler, knower, only the empty process of thinking, feeling, and consciousness, no goer, only going.

- Alan Watts gave an excellent analogy. We assume there is a fist. We can clench five fingers and see it it. Unclench and it disappears. Clench and it reappears. But, say, there is a hand (five fingers like the Five Aggregates of Existence, composite parts not a concrete whole as we assume). Now say we make a fist. Has a fist really come into existence? No, we have a word, a noun, so we assume that is what happens. But when opened we called it a hand, when clenched a "fist." There is no fist, only "fisting," as it were, no hand but only "handing," verbs not nouns, processes not fixed entities. The same is true of the persistent idea/assumption of a self, and so we cling to form (body), feeling (sensations), perceptions, formations, and consciousnesses -- processes, not nouns. But this is only true in an ultimate sense. In a conventional sense, the Buddha and Buddhism very much may speak of a "self." The Five Aggregates describe that self in detail from one life to the next to the next. This is so liable to be misunderstood that it is only taught to advanced students, usually in an intensive setting such as a monastic context, because everyone is so likely not only to misunderstand but then to make wrong assumptions/conclusions based on that misunderstanding. So take it as it is given, as an ultimate teaching (Abhidharma), not a conventional teaching.

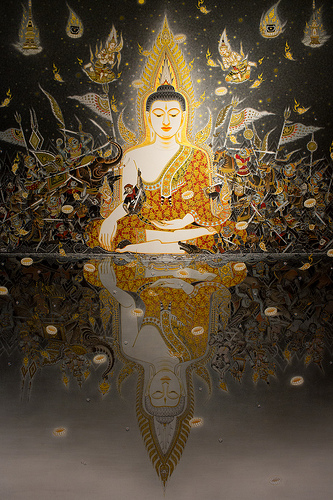

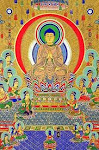

|

| The Buddha, Himalayan sky (Sahil Vohra/flickr) |

The principal cause is ignorance (avijja) and with it craving, which assumes many forms, as we strive to find fulfillment in things, which are in fact empty, unable to fulfill us. (The real solution is wisdom and enlightenment).

Craving impels us to engage in actions (karma) designed to satisfy craving, yet as craving is essentially insatiable the result is rebirth. We wander on life after life, falling to pitiful worlds, coming up again. Suicide is no answer, no solution at all. But it will seem so when our desires are frustrated.

Craving is a powerful mental force latent in all unenlightened beings. The cause of this constant craving is ignorance of the true nature of life: not knowing that life is an ever-changing process, we take it very personally even as it is subject to so much suffering; we cling to something totally devoid of a self or core. All life, wherever it is found, bears this same threefold nature: a process stamped with the Three Marks of impermanence, unsatisfactoriness, and egolessness (anicca, dukkha, anatta).

|

| Sensual craving disappoints |

Craving is a powerful mental force latent in all unenlightened beings. The cause of this constant craving is ignorance of the true nature of life: not knowing that life is an ever-changing process, we take it very personally even as it is subject to so much suffering; we cling to something totally devoid of a self or core. All life, wherever it is found, bears this same threefold nature: a process stamped with the Three Marks of impermanence, unsatisfactoriness, and egolessness (anicca, dukkha, anatta).

The Buddha realized for himself the true nature of life and through this realization of enlightenment and nirvana attained to something beyond life and death: a reality that is unconditioned, blissful, and deathless.

This state cannot be described or comprehended by words and concepts, but it can be experienced and seen directly. It has to be realized inwardly as a matter of direct personal experience; it has to be attained for oneself and by oneself. This ultimate reality, where doubt expires in experience, is nirvana, the goal of the Buddhist path that comes with enlightenment/awakening. More

"No way out!"?

What becomes of people who choose suicide instead? It is usually rebirth in the realm of hungry ghosts or great regret and a loss of a precious opportunity to experience and resolve things in the human world.

The Petavatthu is full of stories about the miserable karmic results of such a choice. Yet many are pulled to it, drawn by inimical beings (who are jealous and envious and wish the downfall of those fortunate enough to currently have a human birth), misled by wrong views, self destructive or sabotaging thought-patterns, misunderstandings of reality...

Real escape from suffering

The Buddha taught, "In truth, there is an unborn, unoriginated, uncreated, unbecome (unformed). If there were not this unborn, unoriginated, uncreated, unbecome, escape from the world of the born, the originated, the created, the formed (becoming), would not be possible" (Inspired Utterances, Udana VIII.3). Where is happiness?

No comments:

Post a Comment